Extreme weather and climate change impacts hit Africa hard

“>

Key Findings

Temperatures

The average surface temperature across Africa in 2024 was approximately 0.86 °C above the 1991–2020 long-term average. North Africa recorded the highest temperature (1.28°C above the 1991-2020 average) and this is the sub-region of Africa which is warming fastest.

Extreme heat hit many parts of the continent during 2024, affecting agriculture, labour productivity and disrupting education.

Sea surface temperatures were the highest on record, ahead of 2023. Particularly large increases in sea surface temperatures have been observed in the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea.

Almost the entire ocean area around Africa was affected by marine heatwaves of strong, severe or extreme intensity during 2024; especially the tropical Atlantic. From January to April, nearly 30 million km² was affected the largest since the start of monitoring in 1993, although the area decreased later in the year.

High ocean temperatures disrupt marine ecosystems and can intensify tropical storms, and combine with sea-level rise to pose additional threats to coastal communities.

Precipitation

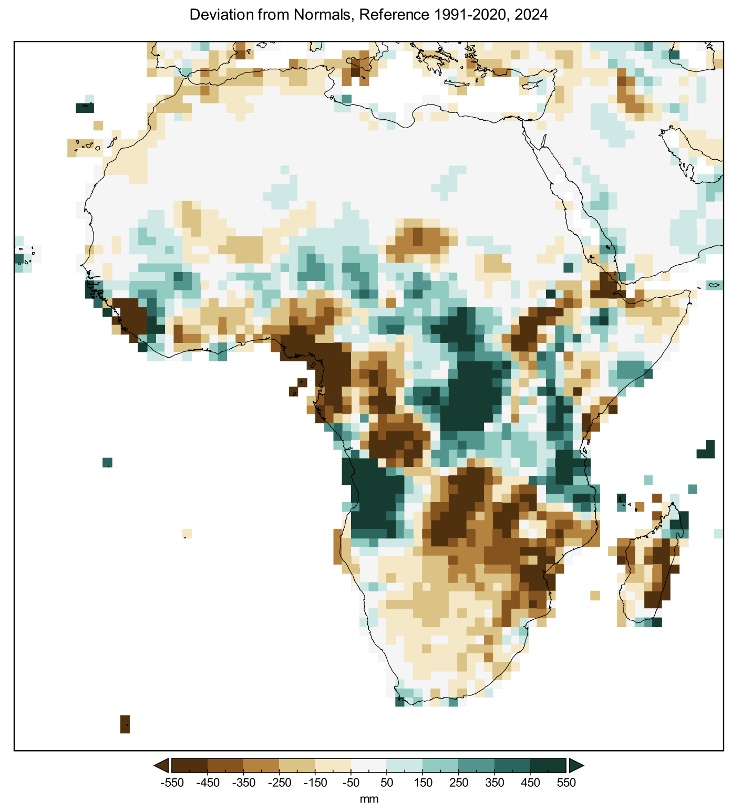

Precipitation anomalies in mm for 2024: Blue areas indicate above-average precipitation, and brown areas indicate below-average precipitation. The reference period is 1991-2020.

Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC)

An El Niño event and positive Indian Ocean Dipole phase, which extended from 2023 into early 2024, played major roles in rainfall patterns.

Southern Africa experienced damaging drought conditions, particularly in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe, which suffered the worst drought in at least two decades. The aggregate cereal yields in southern Africa were 16% below the five-year average – and in the case of Zambia and Zimbabwe 43% and 50%, respectively. Low water levels and low hydropower output from Lake Kariba, Africa’s largest man-made reservoir, caused prolonged power outages and economic disruption.

In East Africa, exceptionally heavy long rains from March to May led to severe flooding in Kenya, Tanzania and Burundi. Hundreds of people lost their lives, and more than 700 000 were affected. Rainfall during the October to December season was below average, raising food security concerns.

West and Central Africa suffered devastating floods that affected over four million people, resulting in several hundred casualties and hundreds of thousands of displacements. Nigeria, Niger, Chad, Cameroon and the Central African Republic were among the hardest hit countries.

North Africa recorded its third consecutive below-average cereal harvest due to low rainfall and extreme high temperatures. Morocco’s output fell 42% below the five-year average after six consecutive years of drought.

Tropical Cyclones

For the first time in the satellite era, two tropical cyclones, Hidaya and Ialy, developed in May and moved over the far north-western part of the basin near Tanzania and Kenya over a region rarely frequented by mature tropical systems.

Tropical Cyclone Chido had devastating effects as it made landfall on Mayotte (France) as the most powerful storm in 90 years to impact the island which forms part of the Comoros archipelago. It then hit Mozambique and Malawi. Tens of thousands of people were affected; many were left homeless and without access to drinkable water.

Digital transformation

Many countries in Africa are embracing digital transformation to improve weather forecasts and early warnings and this has been identified as a regional priority. Artificial Intelligence brings new potential to strengthen service delivery.

For example, the Nigeria Meteorological Agency has embraced digital platforms to disseminate vital agricultural advisories and climate information. The Kenya Meteorological Department provides weather forecasts to farmers and fishers through mobile applications and SMS messages. The South African Weather Service has also integrated AI-based forecasting tools and modern radar systems for effective and timely weather predictions.

In a complementary effort in 2024, 18 NMHSs across the continent upgraded their websites and digital communication systems to enhance the reach and impact of their services, products and warnings.

While these efforts represent important steps towards the digital transformation of weather and climate services, much more is needed to integrate these digital technologies into operational systems throughout the continent, including:

- Increased investment in digital infrastructure and capacity building.

- Stronger data stewardship and sharing frameworks.

- Improved equitable access and inclusive service.